Difference between revisions of "Laser Cooling of Complex Polyatomics"

(Created page with "== Research Overview == The goal of this experiment is to develop techniques to bring polyatomic molecules into the ultracold regime using direct cooling. The use of laser r...") |

(→People) |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[File:SrOH straight at angle.png |right|230 px|Strontium monohydroxide, the primary molecule used in this experiment.]] | ||

== Research Overview == | == Research Overview == | ||

| − | The goal of this experiment is to develop techniques to bring polyatomic molecules into the ultracold regime using direct cooling. The use of laser radiation to control and cool external and internal degrees of freedom has revolutionized atomic, molecular, and optical physics. The powerful techniques of laser cooling and trapping using light scattering forces for atoms led to breakthroughs in both fundamental and applied sciences, including detailed studies of diverse degenerate quantum gases [[#References|[1,2]]], creation of novel frequency standards [[#References|[3]]], and precision measurements of fundamental constants [[#References|[4,5]]]. Polyatomic molecules are more difficult to manipulate than atoms and diatomic molecules because they possess additional rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom. Partially because of their increased complexity, cold dense samples of molecules with three or more atoms offer unique capabilities for exploring interdisciplinary frontiers in physics, chemistry and even biology. Precise control over polyatomic molecules could lead to applications in astrophysics [[#References|[6]]], quantum simulation [[#References|[7]]] and computation [[#References|[8]]], fundamental physics [[#References|[9,10]]], and chemistry [[#References|[11]]]. Study of parity violation in biomolecular chirality [[#References|[12]]]—which plays a fundamental role in molecular biology [[#References|[13]]]—necessarily requires polyatomic molecules. | + | The goal of this experiment is to develop techniques to bring polyatomic molecules into the ultracold regime (T<1mK) using direct cooling. The use of laser radiation to control and cool external and internal degrees of freedom has revolutionized atomic, molecular, and optical physics. The powerful techniques of laser cooling and trapping using light scattering forces for atoms led to breakthroughs in both fundamental and applied sciences, including detailed studies of diverse degenerate quantum gases [[#References|[1,2]]], creation of novel frequency standards [[#References|[3]]], and precision measurements of fundamental constants [[#References|[4,5]]]. Polyatomic molecules are more difficult to manipulate than atoms and diatomic molecules because they possess additional rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom. Partially because of their increased complexity, cold dense samples of molecules with three or more atoms offer unique capabilities for exploring interdisciplinary frontiers in physics, chemistry and even biology. Precise control over polyatomic molecules could lead to applications in astrophysics [[#References|[6]]], quantum simulation [[#References|[7]]] and computation [[#References|[8]]], fundamental physics [[#References|[9,10]]], and chemistry [[#References|[11]]]. Study of parity violation in biomolecular chirality [[#References|[12]]]—which plays a fundamental role in molecular biology [[#References|[13]]]—necessarily requires polyatomic molecules. |

| − | Our approach starts with buffer gas cooling[[#References|[14-16]]], a technique that dramatically reduces the number of internal rotational and vibrational states by thermalizing a sample of molecules with He gas at ~1K. This initial cooling step is critical for working with molecules to limit the number of quantum states that have significant population. We are now working to adapt the laser cooling techniques that were so successful with atoms to work on molecular samples. While atomic species have selection rules that limit the number of states populated by spontaneous decay, | + | Our approach starts with buffer gas cooling [[#References|[14-16]]], a technique that dramatically reduces the number of populated internal rotational and vibrational states by thermalizing a sample of molecules with He gas at ~1K. This initial cooling step is critical for working with molecules to limit the number of quantum states that have significant population. We are now working to adapt the laser cooling techniques that were so successful with atoms to work on molecular samples. While atomic species have selection rules that limit the number of states populated by spontaneous decay, molecules have selection rules for electronic and rotational degrees of freedom but not vibrational degrees of freedom. Therefore, the major complication with molecules is branching to higher vibrational states outside of the cycling transition. |

| − | Motivated the recent success laser cooling and magneto-optical trapping diatomic molecules [[#References|[16-26]]] and | + | Motivated by the recent success in laser cooling and magneto-optical trapping for diatomic molecules [[#References|[16-26]]] and by insights gained in efforts underway in our own lab we have successfully extended Doppler and sub-Doppler cooling techniques to polyatomic molecules. |

| − | We are currently | + | We are currently working to extend laser cooling to larger molecules. We have demonstrated that magnetically induced Sisyphus cooling works for SrOH, but we would like to examine how to generalize this technique for larger, more complex species. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

==People== | ==People== | ||

| − | + | '''Post-docs''' | |

| − | + | * Debayan Mitra | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

'''Grad Students''' | '''Grad Students''' | ||

| − | |||

* Louis Baum | * Louis Baum | ||

| + | * Nathaniel Vilas | ||

| + | * Christian Hallas | ||

| + | * Shivam Raval | ||

'''Undergrads''' | '''Undergrads''' | ||

| − | * | + | * Andrew Winnicki |

'''Former Students and Postdocs''' | '''Former Students and Postdocs''' | ||

| − | * Boerge Hemmerling - Now a postdoc working with Prof Haffner at UC Berkeley | + | * Boerge Hemmerling - Now a postdoc working with Prof. Haffner at UC Berkeley |

| − | * Kyle Matsuda - Now a grad student University of Colorado | + | * Kyle Matsuda - Now a grad student at University of Colorado Boulder |

| − | * Peter Olson - Now | + | * Peter Olson - Now an undergraduate at Washington University |

| − | + | * Alex Sedlack - Now a Harvard alumni | |

| + | * Phelan Yu - Now a grad student at Caltech | ||

==Latest News== | ==Latest News== | ||

| − | === Proposal to Extend Laser Cooling to MOR molecules=== | + | === Proposal to Extend Laser Cooling to MOR molecules === |

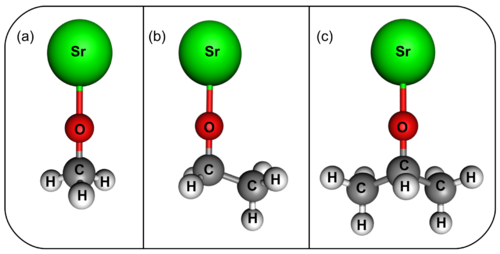

| − | Our proposal to extend laser cooling to MOR molecules has been | + | Our proposal to extend laser cooling to MOR molecules has been published in the Special Issue on Cold Molecules of [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cphc.201601051/full ChemPhysChem]. Our work on SrOH has brought our attention to a class of larger molecules that also possess electronic transitions with short lifetimes and diagonal Franck-Condon factors which make them amenable to direct laser cooling. |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MOR molecules.png |thumb|center|500 px| Examples of MOR molecules: a) strontium monomethoxide, b) strontium monoethoxide, and c) strontium isopropoxide ]] | ||

=== Magnetically Assisted Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH on arXiv === | === Magnetically Assisted Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH on arXiv === | ||

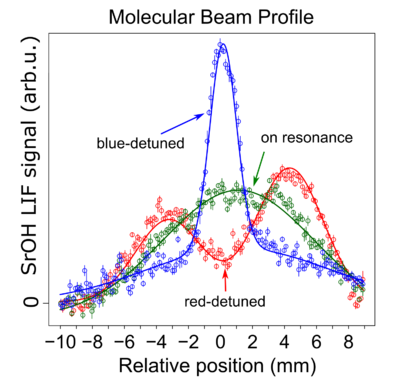

| − | Our work on Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH has been submitted to | + | Our work on Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH has been submitted to PRL. The preprint is available at [https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.02254 arXiv:1609.02254]. This demonstrates that dramatic cooling of polyatomic molecular samples is possible with relatively few scattered photons. In this case we cooled a beam collimated to a transverse temperature of 50 mK to a final temperature of 700 μK. 1-dimensional laser cooling is an important step towards 3-dimensional laser cooling. |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:sisyphus cooled beam.png |thumb|center|400 px| Here we see the effect of magnetically assisted laser cooling vs laser detuning on a molecular beam. The cooled beam (blue) corresponds to a transverse temperature of 700 microkelvin. ]] | |

| + | === Radiation pressure force demonstrated on SrOH=== | ||

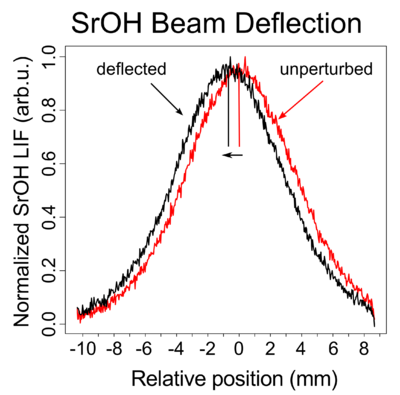

| − | + | Our demonstration of [http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/49/13/134002 Radiation pressure force on SrOH] has been published in the Journal of Physics B as part of the Special Issue on the Atomic and Molecular Processes in the Ultracold Regime, the Chemical Regime and Astrophysics. This is an important step on the road towards laser cooling of polyatomic SrOH. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | [[File:Deflection.png |thumb|center|400 px| Here we see the deflection of a SrOH molecular beam due to radiation pressure force. This deflection of .64 mm corresponds to ~100 scattered photons. ]] | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

#Greif et al. [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/351/6276/953.full.pdf?ijkey=7lDwIMnxRJA5M&keytype=ref&siteid=scij/, Science 351 953 (2016)] | #Greif et al. [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/351/6276/953.full.pdf?ijkey=7lDwIMnxRJA5M&keytype=ref&siteid=scij/, Science 351 953 (2016)] | ||

| − | # Bakr et al. Science 329 547 (2016 | + | # Bakr et al. [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/329/5991/547.abstract Science 329 547 (2016)] |

| − | # Ludlow et al. | + | # Ludlow et al. [http://journals.aps.org/rmp/abstract/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.637 Mod. Phys. Rev. 87 637 (2015)] |

| − | # Fixler | + | # Fixler et al. [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/315/5808/74 Science 315 74 (2007)] |

| − | # Cladé | + | # Cladé et al. [http://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.033001 Phys. Rev. Lett. 96 033001 (2006)] |

| − | #Herbst | + | #Herbst et al.[http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101654 Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 47 427 (2009)] |

| − | #Wall | + | #Wall et al. [http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1367-2630/17/2/025001/meta New J. Phys. 17 025001 (2015)] |

| − | #Tesch | + | #Tesch et al. [http://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.157901 Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 157901 (2002)] |

| − | #Kozlov | + | #Kozlov [http://journals.aps.org/pra/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevA.87.032104 Phys. Rev. A 87 032104 (2013)] |

| − | #Kozlov | + | #Kozlov et al. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/andp.201300010/full Ann. Phys. 525 452 2013] |

| − | #Sabbah | + | #Sabbah et al. [http://science.sciencemag.org/content/317/5834/102 Science 317 102 (2007)] |

| − | #Quack | + | #Quack et al. [http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104511 Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 59 741 (2008)] |

| − | #Quack | + | #Quack [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.200290005/abstract Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 4618 (2002)] |

| − | # | + | #Hutzler et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cr200362u Chem. Rev., 112, 4803 (2012)] |

| − | # | + | #Lu et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c1cp21206k Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 18986 (2011)] |

| − | # | + | #Patterson et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2717178 J. Chem. Phys. 126, 154307 (2007)] |

| − | # | + | #Shuman et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.223001 Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 223001 (2009)] |

| − | # | + | #Shuman et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09443 Nature 467, 820 (2010)] |

| − | # | + | #Hummon et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.143001 Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 143001 (2013)] |

| − | # | + | #Harvey et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.173201 Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 173201 (2008)] |

| − | # | + | #Zhelyazkova et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.89.053416 Phys. Rev. A. 89, 053416 (2014)] |

| − | # | + | #Barry et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature13634 Nature 512, 286 (2014)] |

| − | # | + | #McCarron et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/3/035014 New J. Phys. 17, 035014 (2015)] |

| − | # | + | #Yeo et al.[http://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.223003 Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 223003 (2015)] |

| − | # | + | #Norrgard et al. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.063004 Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 063004 (2016)] |

| − | # | + | #Hemmerling et al. [http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.02787 arXiv:1603.02787] |

Latest revision as of 16:50, 10 March 2020

Contents

Research Overview

The goal of this experiment is to develop techniques to bring polyatomic molecules into the ultracold regime (T<1mK) using direct cooling. The use of laser radiation to control and cool external and internal degrees of freedom has revolutionized atomic, molecular, and optical physics. The powerful techniques of laser cooling and trapping using light scattering forces for atoms led to breakthroughs in both fundamental and applied sciences, including detailed studies of diverse degenerate quantum gases [1,2], creation of novel frequency standards [3], and precision measurements of fundamental constants [4,5]. Polyatomic molecules are more difficult to manipulate than atoms and diatomic molecules because they possess additional rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom. Partially because of their increased complexity, cold dense samples of molecules with three or more atoms offer unique capabilities for exploring interdisciplinary frontiers in physics, chemistry and even biology. Precise control over polyatomic molecules could lead to applications in astrophysics [6], quantum simulation [7] and computation [8], fundamental physics [9,10], and chemistry [11]. Study of parity violation in biomolecular chirality [12]—which plays a fundamental role in molecular biology [13]—necessarily requires polyatomic molecules.

Our approach starts with buffer gas cooling [14-16], a technique that dramatically reduces the number of populated internal rotational and vibrational states by thermalizing a sample of molecules with He gas at ~1K. This initial cooling step is critical for working with molecules to limit the number of quantum states that have significant population. We are now working to adapt the laser cooling techniques that were so successful with atoms to work on molecular samples. While atomic species have selection rules that limit the number of states populated by spontaneous decay, molecules have selection rules for electronic and rotational degrees of freedom but not vibrational degrees of freedom. Therefore, the major complication with molecules is branching to higher vibrational states outside of the cycling transition.

Motivated by the recent success in laser cooling and magneto-optical trapping for diatomic molecules [16-26] and by insights gained in efforts underway in our own lab we have successfully extended Doppler and sub-Doppler cooling techniques to polyatomic molecules.

We are currently working to extend laser cooling to larger molecules. We have demonstrated that magnetically induced Sisyphus cooling works for SrOH, but we would like to examine how to generalize this technique for larger, more complex species.

People

Post-docs

- Debayan Mitra

Grad Students

- Louis Baum

- Nathaniel Vilas

- Christian Hallas

- Shivam Raval

Undergrads

- Andrew Winnicki

Former Students and Postdocs

- Boerge Hemmerling - Now a postdoc working with Prof. Haffner at UC Berkeley

- Kyle Matsuda - Now a grad student at University of Colorado Boulder

- Peter Olson - Now an undergraduate at Washington University

- Alex Sedlack - Now a Harvard alumni

- Phelan Yu - Now a grad student at Caltech

Latest News

Proposal to Extend Laser Cooling to MOR molecules

Our proposal to extend laser cooling to MOR molecules has been published in the Special Issue on Cold Molecules of ChemPhysChem. Our work on SrOH has brought our attention to a class of larger molecules that also possess electronic transitions with short lifetimes and diagonal Franck-Condon factors which make them amenable to direct laser cooling.

Magnetically Assisted Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH on arXiv

Our work on Sisyphus Laser Cooling of SrOH has been submitted to PRL. The preprint is available at arXiv:1609.02254. This demonstrates that dramatic cooling of polyatomic molecular samples is possible with relatively few scattered photons. In this case we cooled a beam collimated to a transverse temperature of 50 mK to a final temperature of 700 μK. 1-dimensional laser cooling is an important step towards 3-dimensional laser cooling.

Radiation pressure force demonstrated on SrOH

Our demonstration of Radiation pressure force on SrOH has been published in the Journal of Physics B as part of the Special Issue on the Atomic and Molecular Processes in the Ultracold Regime, the Chemical Regime and Astrophysics. This is an important step on the road towards laser cooling of polyatomic SrOH.

References

- Greif et al. Science 351 953 (2016)

- Bakr et al. Science 329 547 (2016)

- Ludlow et al. Mod. Phys. Rev. 87 637 (2015)

- Fixler et al. Science 315 74 (2007)

- Cladé et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96 033001 (2006)

- Herbst et al.Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 47 427 (2009)

- Wall et al. New J. Phys. 17 025001 (2015)

- Tesch et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 157901 (2002)

- Kozlov Phys. Rev. A 87 032104 (2013)

- Kozlov et al. Ann. Phys. 525 452 2013

- Sabbah et al. Science 317 102 (2007)

- Quack et al. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 59 741 (2008)

- Quack Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 4618 (2002)

- Hutzler et al. Chem. Rev., 112, 4803 (2012)

- Lu et al. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 18986 (2011)

- Patterson et al. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 154307 (2007)

- Shuman et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 223001 (2009)

- Shuman et al. Nature 467, 820 (2010)

- Hummon et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 143001 (2013)

- Harvey et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 173201 (2008)

- Zhelyazkova et al. Phys. Rev. A. 89, 053416 (2014)

- Barry et al. Nature 512, 286 (2014)

- McCarron et al. New J. Phys. 17, 035014 (2015)

- Yeo et al.Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 223003 (2015)

- Norrgard et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 063004 (2016)

- Hemmerling et al. arXiv:1603.02787